Rocky Mountain National Park: Business Is, Alas, Booming

Published on December 30th, 2016

National Park Service

By Alan Prendergast

December 29, 2016.

WESTWOOD

News that Rocky Mountain National Park's visitor numbers are headed for another record-busting year, with totals for 2016 expected to hit 4.5 million — a whopping 10 percent jump over 2015 — may be a cause for celebration in some quarters, but it's also an occasion for groans and trepidation among those who wonder if the century-old park's most precious features can survive its ever-growing popularity.

On one hand, it's part of the mission of the National Park Service to make the nation's wonders accessible for "public use and enjoyment" by whatever theoretical maximum it can accommodate — and you won't find tourism interests in Estes Park complaining about the crunch. But at the same time, the NPS is supposed to protect its parks from degradation through overuse — a tall order when you've got hundreds of thousands of people descending on the place every month.

RMNP is particularly vulnerable to overuse because of its proximity to urban areas and its relatively negotiable size. It's astonishing to realize that the park is only one-ninth the size of Yellowstone but consistently has more visitors. The three national parks that typically exceed Rocky Mountain in attendance — the Great Smokies, the Grand Canyon and (sometimes) Yosemite — have from two to five times more acreage than it does.

Several years ago, Westword looked at the challenges facing the park in a piece called "Loved to Death." Interviews with park staff and NPS officials, visitors and scientists produced some somber conclusions:

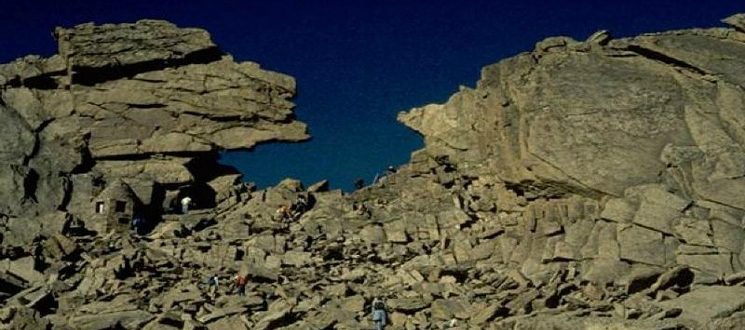

In many ways, the park is being victimized by its own success. Trail Ridge Road and other accessible attractions now draw such crowds throughout the summer that a kind of theme-park atmosphere prevails. Some popular front-country areas are in jeopardy of being loved to death by the throngs at the trailheads. Peak-baggers of all ages and abilities come to Longs Peak in late summer, an endless procession of Gore-Tex-clad penitentes, gasping in the thin air and trudging to the summit. Meanwhile, the quest for wilderness is bringing more and more hikers into backcountry once considered too primitive or remote to worry about.

Most people think of national parks as inviolate sanctuaries, where natural resources are guarded as if under an invisible dome. But Rocky Mountain's experience shows that the protection the parks offer is fragile. Overuse can compromise the very "wilderness values" people are seeking in the park…

Rocky Mountain has become a living laboratory for studying the effects of 21st-century civilization on wilderness — and a focal point in the debate over what to do about it. Can wilderness survive, in any meaningful way, with three million visitors a year and another three million polluting neighbors at its doorstep?

Since those words were written in 2004, the visitor numbers have increased by 50 percent. For every two people on the trails a decade ago, there are now three.

The park administration has, of course, taken various steps to meet the onslaught. Increased fees have helped fund needed upgrades and repairs. The use of shuttles to ferry people to popular trailheads helps to reduce traffic. Encouraging visitors to check out the comparatively empty west side of the park helps, too. More people are figuring out that the shoulder months, early spring or late fall, or even the middle of winter are better bets for experiencing something close to nature in a place that can be simply unbearable in mid-summer. But there's no denying that the growth the park is experiencing now is unsustainable in the long haul.

Back in 1915, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the legislation creating Rocky Mountain National Park, it seemed inconceivable that such a vast and wild place — 114 named peaks above 10,000 feet, 147 lakes, the headwaters of several river systems flowing down either side of the Continental Divide, hundreds of species of plants and birds, as well as black bears, deer, bighorn sheep, mountain lions and moose — could ever be fully embraced, much less overrun. Whether the park can make it through its second century without being fully domesticated and trashed will depend on some hard choices in the years ahead.

Alan Prendergast has been a staff writer for Westword since 1995 and teaches journalism at Colorado College. His stories about the justice system, historic crimes, high-security prisons and death by misadventure have won numerous awards and appeared in a wide range of magazines and anthologies.