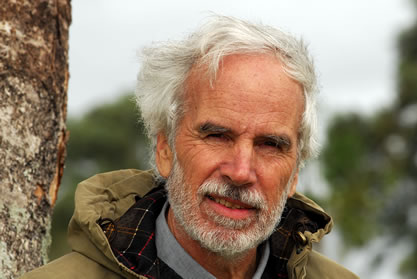

Remembering Douglas Rainsford Tompkins, 1943-2015

Published on December 18th, 2015

Global Conservation Cause Loses a Giant to South American Kayaking Accident

|

| Douglas Rainsford Tompkins, 1943-2015 |

Doug Tompkins was Ohio-born and New York-bred but a Californian at heart. The former entrepreneur and mogul – founder and cofounder of two highly profitable, fashionable companies, The North Face and Esprit – was a passionate outdoorsman and historic champion of conservation in the mold of fellow Californians John Muir and David Brower.

Like those two conservation icons, Tompkins was a tireless advocate for wilderness, wildlife and biodiversity. Unlike them, due to his lucrative business career, he had the financial means to actually buy and preserve vast tracts of threatened wildlands, protecting them as national parks and private nature reserves. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Edward Humes referred to Tompkins as one of a new breed of “Eco Barons.” Well, perhaps not so new; the Rockefellers pioneered conservation philanthropy in the early 20th century, and public land trusts continue that important work today.

Like David Brower, Doug Tompkins believed that human overpopulation is an existential threat to the planet. He believed overconsumption was as well. That’s why he eventually turned his back on the business world, where he felt he was making money by encouraging an unsustainable consumerism: foisting products on people that they didn’t really need. He quit business, as Tompkins himself said, because it was time “to pay his rent for living on the planet.”

The Washington Post described his extraordinary transition this way:

“In 1985, Douglas Tompkins was the millionaire cofounder of two successful clothing companies, the North Face and Esprit. He was courted by magazine editors and politicians, revered by the San Francisco hippie elite. Girls’ fashion – incredibly, for a man who dressed every day in the same old polo and blue jeans – turned on his company’s marketing campaigns.

“By 1990, he gave it all up and moved to the end of the world.”

|

| On a rare, clear day, Monte Fitz Roy juts skyward on the Chilean-Argentinian border, in the southern Andes, or Patagonia. In 1968, Tompkins and his team forged a new route to the summit, the “California Route.” |

The 72-year-old Tompkins perished December 8 in a freak kayaking accident in General Carrera Lake in Chilean Patagonia, near the “end of the world” in the southern tip of South America. He first explored this untamed, breathtaking region nearly half a century ago, in 1968, with his lifelong climbing and surfing buddy Yvon Chouinard, founder of the outdoor apparel and equipment company Patagonia. Tompkins, Chouinard and partners forged a new climbing route up Monte Fitz Roy, one of Patagonia’s signature mountains. It was only the third time Fitz Roy had ever been climbed.

At the time of the December 8 accident, Tompkins was on an excursion with a group that included some of his old friends, among them Chouinard; Rick Ridgeway, one of the first Americans to summit the Himalayan peak K2, the world’s second-highest mountain; Lorenzo Alvarez, owner of the adventure travel outfitter, Bio Bio Expeditions; Jib Ellison, founder and CEO of sustainability consulting firm Blu Skye; and river conservation advocate Weston Boyles.

General Carrera Lake is the second largest in South America. Fed by glacial runoff from the Andes, the temperature of its water is a frigid 39° F, even in summer months. Mountains climb on all sides and the weather can be treacherous, suddenly twisting from calm and sunny to windy and snowing.

This is what happened the day of the accident. The wind picked up and gusts reached 40 mph or more; waves grew abruptly to nine feet. Tompkins and Ridgeway’s kayak capsized. While they were eventually rescued by a helicopter, Tompkins had spent more than an hour in that freezing water, lost consciousness and succumbed to hypothermia.

It is ironic indeed that after “cheating death” countless times on risky mountaineering expeditions around the world, this rugged explorer’s life should be claimed while enjoying what was supposed to be a relaxed kayak camping trip with old friends. Perhaps over time, the odds simply get even. Or as Bilbo Baggins learned the hard way in J.R.R. Tolkien’s classic The Hobbit, authentic adventure is inherently unpredictable; it can make you late for dinner…or much worse. And Doug Tompkins was an adventurer through and through. To the end of his life, he embodied the philosophy of the slogan he coined for North Face: “never stop exploring.”

|

| Doug and Kris Tompkins |

Through their various charities, Tompkins and his wife, Kristine McDivitt Tompkins, have acquired about 2.2 million acres of wildlands in South America. Part of this acreage comprises Pumalin Park in southern Chile, the largest private nature reserve on Earth. The Tompkinses have helped create five new national parks in Chile and Argentina, expand another, and have been working to establish several more.

As a Peace Corps Volunteer in Central America a quarter century ago, I worked to help establish national parks and protected areas in Honduras, so I can appreciate all the more the sheer, wondrous magnitude of what the Tompkinses have accomplished.

As an American citizen and as an immigrant to Chile, Tompkins’ land purchases and environmental activism were initially quite controversial among some Chileans. All manner of crazy rumors as to his supposedly nefarious intentions were spread at first. However, he persevered and eventually he collaborated with two Chilean presidents of different political parties to establish national parks. His steadfast resolve led to similar success and growing support in Argentina.

Tompkins’ funding and strategic input in the multiyear campaign to stop a massive hydroelectric scheme that would have dammed a number of wild rivers in Chilean Patagonia was crucial and won him additional supporters and admirers. That campaign eventually succeeded due to the tenacity of dam opponents.

Tompkins was inspired by the Norwegian eco-philosopher Arne Naess, one of the founders of the “deep ecology” movement (as was CAPS advisor George Sessions, professor at Sierra College). Along with author and activist Jerry Mander, in 1990 Tompkins created the Foundation for Deep Ecology. He believed that a superficial environmentalism is destined to fail. Only with profound structural changes to society and economies could humankind avert its hastening plunge toward what he called “the dustbin of history.” Tompkins was a strident critic of “megatechnology,” and he dedicated considerable funding to scrutiny and criticism of it.

Tompkins advocated the adoption of an “ecocentric” ethic, that is, a belief that we humans are members of the community of life, not its overlord. This is reminiscent of American conservationist Aldo Leopold’s land ethic, as described in the final essay of the conservation classic A Sand County Almanac, “The Land Ethic:”

“…a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.”

As I mentioned above, Tompkins was also an ardent supporter of the population cause. In 2015, his Foundation for Deep Ecology published the poignant and well-received, large format book of stunning photos and essays Overdevelopment, Overpopulation, Overshoot. Tompkins was the art director for this project.

In an email exchange Doug and I had in June 2015, he wrote:

“Doesn’t arguing about who bears the greatest responsibility, the over consumers or the over populators, seem to be both irrelevant itself and small minded? It is not an important question, and it is taking precedence over far more urgent questions and the need for positive action by all humans in every corner of the world to see if indeed it is possible to head off global ecological collapse and its obvious consequences.”

Doug’s sudden death has hit his wide circle of friends and colleagues very hard. A larger-than-life figure has been abruptly stolen from us. At a holiday party the very day Doug died, one of his good friends, clearly very shaken, told me of his preparations to fly to South America the next day to commiserate with family and friends and to pay his final respects to the man he revered.

Doug’s New York-based friend, Lorna Salzman, a long-time environmental activist and writer who worked for a decade as a regional representative for Friends of the Earth under its founder David Brower, wrote:

“I realize why I am grieving so much at Doug’s death. Though I only met him once we have corresponded often. Doug was special because he not only had great ideas and insights himself but was wide open to the thoughts of others and really listened to other people….The loss of Doug is like the loss of wilderness. Even though there are wildernesses I will never see, I mourn their destruction. In this same way, though I was not likely to see Doug again, the fact that he is no longer with us is as grievous as the loss of wilderness, species and Nature. Even if I never saw him again, just knowing he was out there, like the wilderness, was comforting.”

Yet Doug Tompkins’ conservation legacy will surely survive his untimely passing. The land and the creatures he helped save and the thousands of activists he inspired will endure.

As the website of Tompkins Conservation declares: “The Work Goes On:”

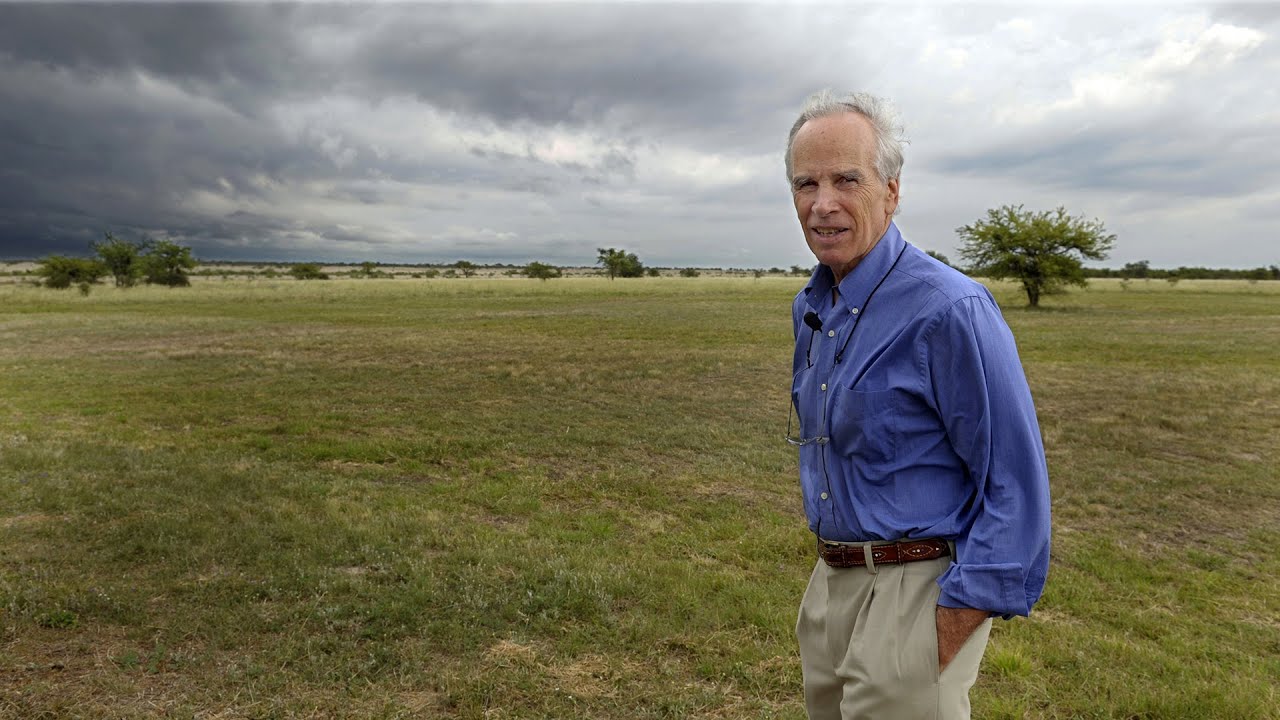

|

| Douglas Tompkins on his property in Corrientes Province, Argentina, in 2009. |

“While Kris Tompkins is heartsick over Doug’s loss, she has made her wishes clear: ‘working with President Bachelet in Chile and president-elect Macri in Argentina we will continue – and even accelerate – our work to create new national parks.’ The legacy of Douglas Tompkins does not end with his final trek into the wilderness but will live on in the wild habitat, wild creatures, and wild beauty he helped sustain – and in the places that conservationists mentored by him or inspired by his example will protect in the future.”