Hail Cesar!

Published on March 31st, 2017

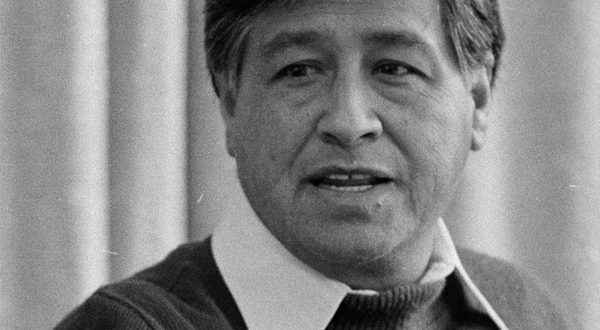

Cesar Chavez in 1979 (Photo: Library of Congress)

By Mark Krikorian

March 31, 2017

The National Review

Honor the Farm Workers leader’s 90th birthday with National Border Control Day.

On March 31, 1927, Cesar Estrada Chavez was born in Yuma, Ariz., to parents who had come north from Mexico as children in the 1890s. He went on to found the United Farm Workers union, and by his death in 1993 had become an icon for Hispanic activist groups and the Left in general.

And his views on border control would be a perfect fit in the Trump administration. As a child working with his family in the California fields, Cesar quickly learned the reason farmworkers were paid so little and treated so poorly: As his biographer Miriam Pawel writes, “a surplus of labor enabled growers to treat workers as little more that interchangeable parts, cheaper and easier to replace than machines.”

Chavez acolytes today try to explain away his hawkish pro-border views as coming from a different historical context, applicable only to specific strikes and the strike-breakers that farmers tried to import. But this is false.

In fact, even before he started the union and fought against illegal immigration, he was opposed to the bracero program, which legally imported cheap, disposable labor from Mexico at the expense of American citizens (of Mexican and other origins) who had been working in the fields. Pawel quotes Chavez as saying, “It looks almost impossible to start some effective program to get these people their jobs back from the braceros.”

Congress ended the bracero program in 1964, and the next 15 years were the salad days, as it were, for farmworkers — until illegal immigration became so pervasive (despite Chavez’s efforts) that workers lost all bargaining power.

But during those 15 years, Chavez fought illegal immigration tenaciously. In 1969, he marched to the Mexican border to protest farmers’ use of illegal aliens as strikebreakers. He was joined by Reverend Ralph Abernathy and Senator Walter Mondale.

In the mid 1970s, he conducted the “Illegals Campaign” to identify and report illegal workers, “an effort he deemed second in importance only to the boycott” (of produce from non-unionized farms), according to Pawel. She quotes a memo from Chavez that said, “If we can get the illegals out of California, we will win the strike overnight.”

The Illegals Campaign didn’t just report illegals to the (unresponsive) federal authorities. Cesar sent his cousin, ex-con Manuel Chavez, down to the border to set up a “wet line” (as in “wetbacks”) to do the job the Border Patrol wasn’t being allowed to do. Unlike the Minutemen of a few years ago, who arrived at the border with no more than lawn chairs and binoculars, the United Farm Workers patrols were willing to use direct methods when persuasion failed. Housed in a series of tents along the Arizona border, the crews in the wet line sometimes beat up illegals, the “cesarchavistas” employing violence even more widely on the Mexican side of the border to prevent crossings.

None of this was unknown to or opposed by Cesar Chavez. As Pawel notes, “As always, Cesar protected Manuel at all costs. . . . Manuel was willing to do ‘the dirty work,’ Cesar acknowledged.” At one UFW meeting, Dolores Huerta, co-founder of the union with Chavez and always a more conventional leftist than he, foreshadowed today’s anti-borders agitators, objecting to the words “wetback” and “illegal”: “The people themselves aren’t illegal. The action of being in this country maybe is illegal.” Pawel relates Chavez’s response, from a tape recording of the meeting: “Chavez turned on Huerta angrily. ‘No, a spade’s a spade,’ he said. ‘You guys get these hang-ups. Goddamn it, how do we build a union? They’re wets, you know. They’re wets, and let’s go after them.’”

Chavez’s vigilantism is unacceptable in a country ruled by law; in any case, the Border Patrol is both able and permitted (since January 20, anyway) to do its job. But neither Chavez’s occasional use of violence against illegals nor his later descent into cultism and paranoia detract from one of the core messages of his professional life: Flooding the labor market with people from abroad undermines American workers trying to improve their lot in life. For this we should honor his memory — by celebrating his birthday as National Border Control Day.

Hail Cesar! —

Mark Krikorian is the executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies.