Brown’s Arid California, Thanks Partly to His Father

Published on May 18th, 2015

Adam Nagourney

May 16, 2015

The New York Times

LOS ANGELES — When Edmund G. Brown Sr. was governor of California, people were moving in at a pace of 1,000 a day. With a jubilant Mr. Brown officiating, California commemorated the moment it became the nation’s largest state, in 1962, with a church-bell-ringing, four-day celebration. He was the boom-boom governor for a boom-boom time: championing highways, universities and, most consequential, a sprawling water network to feed the explosion of agriculture and development in the dry reaches of central and Southern California.

Nearly 50 years later, it has fallen to Mr. Brown’s only son, Gov. Jerry Brown, to manage the modern-day California that his father helped to create. The state is prospering, with a population of more than double the 15.5 million it had when Mr. Brown, known as Pat, became governor in 1959. But California, the seventh-largest economy in the world, is confronting fundamental questions about its limits and growth, fed by the collision of the severe drought dominating Jerry Brown’s final years as governor and the water and energy demands — from homes, industries and farms, not to mention pools, gardens and golf courses — driven by the aggressive growth policies advocated by his father during his two terms in office.

The stark challenge that confronts this state is putting a spotlight on a father and son who, as much as any two people, define modern-day California. They are strikingly different symbols of different eras, with divergent styles and distinct views of government, growth and the nature of California itself.

|

| Edmund G. Brown Sr. in San Francisco after his election in 1958. Credit Nat Farbman/The LIFE Picture Collection–Getty Images |

Pat Brown, who died in 1996 at the age of 90, was the embodiment of the post-World War II explosion, when people flocked to this vast and beckoning state in search of a new life. “He loved that California was getting bigger when he was governor,” said Ethan Rarick, who wrote a biography of Pat Brown and directs the Robert T. Matsui Center for Politics and Public Service at the University of California, Berkeley. “Pat saw an almost endless capacity for California growth.”

Jerry Brown arrived in Sacramento for the first of two stints he would serve as governor in 1975 — just over eight years after Pat Brown was defeated for re-election by Ronald Reagan. He was, at 36, the austere contrast to his father, a product of the post-Watergate and post-Vietnam era, wary of the kind of brawny, interventionist view of government that animated Pat Brown. The environmental movement had emerged in the years between Pat Brown’s defeat and Jerry Brown’s arrival — the first Earth Day and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries oil embargo took place during that period — and among its most passionate adherents was Pat Brown’s son.

If Pat Brown wanted the stunningly ambitious California State Water Project that he muscled into law to “be a monument to me,” as he later said of what was the most expensive public works project in the state’s history, Jerry Brown championed the modest if intellectually provocative “Small Is Beautiful” viewpoint espoused by the economist E. F. Schumacher, which emphasized the dangers of depleting natural resources. (Mr. Brown flew to London to speak at Schumacher’s funeral in 1977.) As governor, Jerry Brown spoke of limits and respect for the fragility of the planet from the moment he took office.

“He positioned himself as very, very different from my father,” said Kathleen Brown, who is Mr. Brown’s youngest sister. “Some looked at it as a psychological battle between father and son. I don’t think it was that at all. I think it was a coming-of-age in a different period. The consciousness that our resources were limited was just beginning to take hold in the broader community.”

Since taking office as governor for the second time, in 2011, Jerry Brown has again been the voice of limits — though this time, his view is informed less by the theories of environmentalists and more by the demands of trying to manage a drought of historic proportions. One month Mr. Brown is ordering a 25 percent reduction in the use of potable water in urban communities; the next he is pressing for a 40 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions to battle the choking pollution that is another byproduct of the heady growth.

“We are dealing with different periods,” Mr. Brown said in an interview. “The word ‘environment’ wasn’t used then: You talked about conservation. Environmentalism came in after my father left. There was this sense that we can become No. 1 ahead of New York — they rang church bells when we did — but now, you fast-forward 60 years later, and people are concerned about whether the water is available, the cost to the environment, how to pay for suburban infrastructure.”

“All of these insights and concerns developed after most of his governorship,” Mr. Brown said of his father. “But they preceded mine — and they have intensified.”

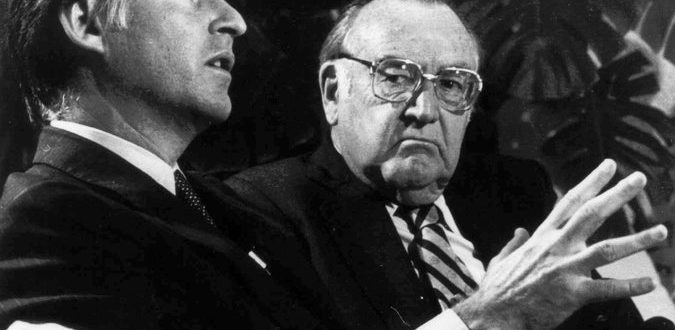

|

| Jerry Brown visiting his father in 1960. Credit Associated Press |

Pat and Jerry Brown are at once products, advocates and shapers of the California dream — with no shortage of the attendant complexities and tensions that emerge when governance and family mix. Friends recall the tension when Jerry Brown first came into office, rarely mentioning his father or consulting him for advice. Kathleen Brown said family dinners could be contentious affairs. “They debated everything,” she said.

Now Mr. Brown speaks often of his family’s history in California since it arrived here in 1852, and he warmly shared reminiscences about his father’s tenure. “It’s fun talking about these things,” he said at one point. More than anything, Mr. Brown, 77, disputed the notion that he was cleaning up any mistakes his father made.

“I don’t think he had any alternative,” he said. “The people were arriving. The in-migration was tremendous. The post-World War II mobility. People were moving out here. We didn’t know how the future was going to unfold.”

The House That Pat Built

When Pat Brown, then 53 and the state attorney general, was elected governor in 1958, the Republicans controlled both houses of the Legislature and most statewide offices. He swept to victory in an election that signaled a new direction for California: Brown was a Republican turned Democrat who identified with the New Deal policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“He really in many ways built the modern California that we know,” said Raphael J. Sonenshein, the executive director of the Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Institute for Public Affairs at California State University, Los Angeles. “Even though he only had two terms, they were enormously consequential. I have to think that the California that we live in bears his stamp more than that of any other governor.”

The new governor pledged in his inaugural address to follow “the path of responsible liberalism.” He rejected warnings from aides about the state’s deficit, and advocated tax increases to finance spending on school construction, parks and transportation. During his years in power, the state built three new campuses for the University of California and six more for the state college system — though that was not his top interest.

|

| Clockwise from left: Farmworkers in Burbank in the early 1950s; the Cahuenga Pass Highway; a housing development in Los Angeles in midcentury; and home construction in Pomona. The population has more than doubled since Edmund G. Brown Sr. became governor. Credit Clockwise from left, Margaret Bourke-White/The LIFE Picture Collection–Getty Images; Andreas Feininger/The LIFE Picture Collection–Getty Images; Loomis Dean/The LIFE Picture Collection–Getty Images; J. R. Eyerman/The LIFE Picture Collection–Getty Images |

“Water was the No. 1 thing on his agenda,” said Martin Schiesl, a professor emeritus of history at California State University. In his first year in office, Pat Brown persuaded the Legislature to pass and send to voters a $1.75 billion bond to begin the state water project — a network of dams, pipes and an aqueduct designed to take water from the relatively wet north to Southern California, where 80 percent of the population lived.

Pat Brown was offering an ambitious vision of California as he campaigned across the state for the measure: California as its own vast and diverse nation, where the water of the north would feed the population and farm growth to the south. “He thought it was irresponsible not to plan for the growth that was coming,” Kathleen Brown said. “He used to say, ‘If you don’t want to manage and build for this growth today, we’ll have to do something else tomorrow.’ ”

In a letter cited in “California Rising: The Life and Times of Pat Brown,” the biography by Mr. Rarick, Pat Brown argued that he had no choice. “What are we to do? Build barriers around California and say nobody else can come in because we don’t have enough water to go around?”

Those decisions have led to questions 50 years later, of whether those policies set the stage for the problems that confront California. Marc Reisner argued in “Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water,” his widely respected book on Western water battles, that Pat Brown, who was from Northern California, deliberately pushed a water system designed to encourage population growth in Southern California.

But Pat Brown’s children, as well as historians, said those policies were intended to accommodate — rather than encourage — a march on California that was already taking place. “I suppose we could have built fewer water projects and somehow discouraged growth,” Mr. Rarick said. “We also could have built fewer schools in Southern California. Or built fewer roads.

“I don’t think that’s what societies do,” he said. “Societies try to address the problems that they face.”

Mr. Sonenshein, the director of the institute at California State University, said there was little talk of long-term planning in Pat Brown’s era. “I don’t blame Pat Brown for that,” he said. “But to have a water project that builds the state into a massive power, almost a nation, of course that creates problems. Imagine the problems that we would have had had that not been done.”

A New Tone

Jerry Brown did not originally go into the family business, spending his years as a young man as a Jesuit studying for the priesthood. He spent three years in the seminary, before emerging to prepare for law school and what would prove to be an almost- unbroken lifetime in public office. When he became governor, he arrived in the shadow of his father, who had gone from having an outsize reputation to a second-term decline and defeat in 1966 as he struggled with student unrest at Berkeley and a conservative shift by the electorate.

|

| Jerry Brown as governor in 1975. Credit Associated Press |

Jerry Brown’s new tone was clear from his first inaugural address as he warned of “the rising cost of energy, the depletion of our resources, the threat to the environment, the uncertainty of our economy and the monetary system, the lack of faith in government, the drift in political and moral leadership.”

With one notable exception — he campaigned, unsuccessfully, to win voter support for another water tunnel to finish his father’s project, which to this day he calls essential to the state’s long-term health — this would not be an administration about building roads, bridges, dams or college campuses. Instead, Mr. Brown focused on policies that regulated growth.

“First you had to ask the question: Should we do everything we have always done because that’s the way we have done it?” said Michael Picker, who served as an aide in Jerry Brown’s first administration and is now his appointee as head of the California Public Utilities Commission. “There was a slew of people who were reacting and trying to figure out what the future looked like. We weren’t thinking about economic growth the same way people were before.

“You had Pat Brown, who came up in an era when people were really focused on an extension of the post-World War lifestyle,” Mr. Picker said. “And you had Jerry Brown, who was dealing with people who were looking much more to the future.”

Kathleen Brown said her brother was trying “to shift and tilt the direction of government away from government solving the problem, building big buildings.”

“He thought there was enough,” she continued. “People needed a rest.”

California would quickly learn how stylistically different Jerry Brown was from his father. Pat Brown was a glad-handing, boisterous politician, loud and exuberant. Jerry Brown was cerebral, spiritual, at times prickly and unconventional, ruminating, for example, about how California could engage in space exploration.

“Pat Brown was very gregarious and charismatic and loved to engage with anybody in a very sort of old-style political never-met-a-stranger way,” said Diana S. Dooley, the secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency, who served in Jerry Brown’s first administration as legislative director. “Jerry is every bit his equal in his interest in other people, but he’s very issue-focused. His conversations are always about ‘What are you doing, where are you going, what are you thinking?’ Not ‘How are you, how are your kids?’ ”

|

| Gov. Jerry Brown after detailing his 2015 budget plan in January. “The times set the agenda,” he said in an interview. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York Times |

To this day, with Jerry Brown back in Sacramento, there is a phrase he likes to use about the challenges of governing, as recounted by Ms. Dooley: “We don’t have problems to be solved, we have conditions to be managed. And we are managing the conditions of our time.”

“Pat Brown managed the conditions of his time, with its huge appetite for science and innovations and application to a new generation of parents after the horror of World War II,” Ms. Dooley said. “And Jerry is managing some of the conditions that resulted from that growth.”

Still, if Jerry Brown is different as a governor from his father, he is different from what he was 40 years ago as well. Even as he talks about strains on California, he is championing the kind of big projects that his father was known for: a high-speed train line from San Francisco to Los Angeles and two massive underground pipelines. The pipelines would help convey water through the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, east of San Francisco, to central and Southern California — the state water project his father began.

Some of that, no doubt, reflects the consideration of a man who realizes he has only so many years left in office. “Jerry has appreciated, as time has passed, that leaving a legacy as a political figure often requires concrete,” Kathleen Brown said. “My father’s legacy is very much tied and identified with building. Jerry’s first term was very much more about ideas and fundamental shifts in the focus of government.”

Still, Mr. Brown said he would have done what his father did if he had been governor during Pat Brown’s era — and expected that his father would be doing the same thing Jerry Brown is doing were he running the state today.

“What else could you do?” he said. “Who sets the agenda? The times set the agenda. It’s not like I don’t have a lot of things I want to do. There are a lot of challenges — you have to respond, whether it’s water or drought or education. Health. Immigration. Here they are — do something. That’s what I do. I think my father would do the same thing.”

A version of this article appears in print on May 17, 2015, on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: Brown’s Arid California, Thanks Partly to His Father.