Conservation is More Complicated Than it Used to be

Published on November 29th, 2013

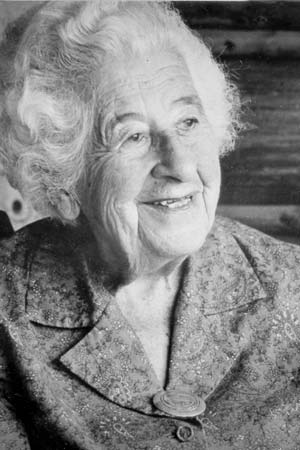

Thanks to a friend of mine in New Mexico – veteran Western river-runner, naturalist, teacher and author Verne Huser – I recently got to re-watch a great documentary about a great conservationist. The great conservationist is the late Margaret Murie (1902-2003), and the great documentary is Arctic Dance: The Mardy Murie Story, a film by Bonnie Kreps and Charles Craighead, narrated by actor Harrison Ford.

Thanks to a friend of mine in New Mexico – veteran Western river-runner, naturalist, teacher and author Verne Huser – I recently got to re-watch a great documentary about a great conservationist. The great conservationist is the late Margaret Murie (1902-2003), and the great documentary is Arctic Dance: The Mardy Murie Story, a film by Bonnie Kreps and Charles Craighead, narrated by actor Harrison Ford.

Back in the early 2000s, I saw Ms. Kreps present Arctic Dance in person at the Smithsonian when it first came out. The film was an inspiring tribute to the life and achievements of this down-to-earth, self-effacing woman – gentle but made of stern stuff, like steel. She had long been dubbed the “Grandmother of the Conservation Movement.”

Margaret Thomas was born in Seattle and raised in Fairbanks, Alaska, back when it was little more than an isolated frontier village on the edge of the vast Alaskan wilderness. In 1924, she became the first woman to graduate from the University of Alaska. That same year she married U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Olaus Murie. The newlyweds honeymooned in the remote upper Koyukuk River region, journeying by dogsled while conducting research on caribou.

But the Muries were not content with research alone when both wildlife and wilderness were threatened by ever-expanding human encroachment. Olaus had been a founder and president of the Wilderness Society, and in 1956, both Muries initiated a campaign to preserve what is now the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). They enlisted Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas to help persuade President Dwight D. Eisenhower to establish ANWR.

After Olaus’ death in 1963, Mardy soldiered on. She worked tirelessly toward the passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) in 1980. ANILCA added 44 million acres to the National Park System and 54 million acres to the National Wildlife Refuge System, including many new acres of designated wilderness. As one who has professionally worked on and personally enjoyed the enormous national parks and national wildlife refuges of Alaska, I am deeply appreciative.

Yet in this day and age of pervasive, insidious threats to ecosystem integrity, wilderness and biodiversity, merely “setting aside” wild areas from development or exploitation is no guarantee they will be “saved.” ANWR faces the ongoing threat of oil extraction on a fraction of its coastal plain, but the much larger threat it and every other intact ecosystem in Alaska faces is climate change.

According to the EPA, during the past half-century, Alaska warmed at twice the national rate, its temperature increasing 3.4°F and winter temperatures by 6.3°F. Average annual temperatures are projected to rise another 3.5 -7°F by 2050.

As Alaska’s climate warms, its renowned landscape-clawing glaciers are melting, shriveling and retreating. Shrubs invade the tundra, displacing lichens and other tundra flora. The caribou that the Muries studied depend on lichens in the winter, and their disappearance may lead to population declines of this critical food source for bears and wolves, as well as for Alaska Natives. Grizzly bears are displacing polar bears and eating muskox.

Raised temperatures and reduced summer moisture are exacerbating drought, wildfire and insect infestation, devastating Alaska's boreal forests of white and black spruce. Flora and fauna and invasive species migrate northward and get jumbled together, with unpredictable outcomes.

How much of the foregoing represents “harm” and how much merely represents “change” is unclear. But rapid rates of change alone, without time for adaptation, can be injurious or disruptive.

What is happening in Alaska is happening elsewhere, including California. Parks and nature preserves – set aside and supposedly saved from development – are nonetheless beset by toxics, invasives, acid rain, noise, poaching, air and water pollution, traffic congestion, overcrowding, encroaching commercialism and other external forces beyond their control.

Unless we are up to the challenge, the very real triumphs of an earlier generation of conservation giants like Mardy Murie will amount to little more than ephemeral sand castles obliterated by a rising tide.