Chávez Stood for Border Security

Published on March 31st, 2014

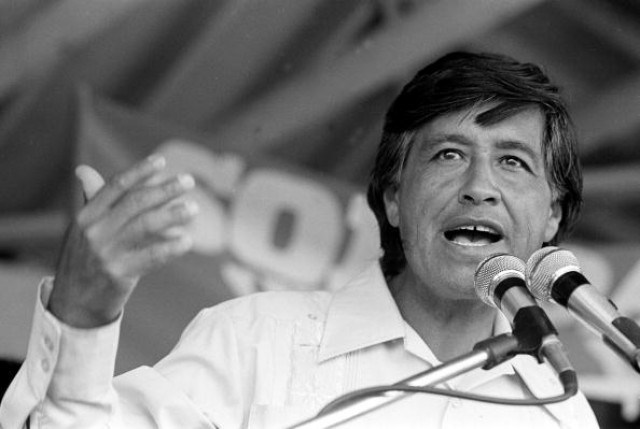

The National Park Service is planning to establish a national park in California honoring César Chávez, the iconic Mexican-American labor leader. Belinda Faustinos, who co-chaired the panel to select the sites for the park, said that it would be a place where Latinos can relate to their culture and history.

The National Park Service is planning to establish a national park in California honoring César Chávez, the iconic Mexican-American labor leader. Belinda Faustinos, who co-chaired the panel to select the sites for the park, said that it would be a place where Latinos can relate to their culture and history.

Actually, it is not just Latinos who can pay respect to Chávez, but Americans of all backgrounds who believe in the integrity of our borders and the right of American workers to aspire to a decent standard of living. As a labor union organizer, Chavez understood that a steady flow of illegal aliens seeking jobs would undermine his efforts to unionize farm workers in California and increase their wages.

Chávez backed his convictions with action. In 1969 he led a march to the Mexican border to protest illegal immigration. He also ordered members of his United Farm Workers union to report illegal aliens working in the fields to immigration authorities. In 1973 he appointed his brother to organize patrols along the border to discourage illegal crossings.

In testimony before Congress in 1979, Chávez complained that “. . . when the farm workers strike and their strike is successful, the employers go to Mexico and have unlimited, unrestricted use of illegal alien strikebreakers to break the strike. And for over 30 years the Immigration and Naturalization Service has looked the other way and assisted the strikebreaking.”

Today, many Latinos who support open borders try to claim Chávez as one of their own, notwithstanding his stance against illegal immigration. To do so, they maintain that later in his career Chávez softened his views on this subject – even going so far as to endorse the amnesty for illegal aliens that Congress passed in 1986.

But even if he did so, that doesn’t prove he decided to favor open borders. Supporters of the 1986 amnesty promoted it as a one-time humanitarian step in exchange for effective new laws which would secure the border once and for all. That assurance was at least possible to believe then, and Chavez may have believed it. Now, after more than a quarter century of betrayals, it is impossible to trust amnesty promoters when they promise enforcement.

In any case, the labor leader was right about the impact of illegal immigration on farm workers. Initially the efforts of his union to improve wages of farm workers brought some significant gains, but the waves of illegal immigration before and after the 1986 amnesty have long since erased most of those improvements.

When the César Chávez National Park is opened, it would be most useful if exhibits there would provide an honest portrayal of his views on border security and its impact on the well-being of U.S. workers. Now more than ever, citizens of all backgrounds need to consider this issue.